The Society for the Suppression of Music was sprung upon an unsuspecting Cincinnati in November 1879. The newspapers carried a brief classified item that conveyed the flavor of the new organization:

Society for the Suppression of MusicApplications for membership in the above society are coming in rapidly – among the latest are Edward Goepper, Wm. W. Taylor, Bellamy Storer, C.F. La Motte, and Frank A. Lee. The reason these well known (former) devotees of Calliope have joined may be learned from the parties themselves by anyone curious to know. The society is now in a flourishing condition, and numbers among its members some of the best of our citizens. Persons desirous of joining should address without delay Judge Longworth, President, or Jno. S. Woods, Treasurer, who will furnish all information on the subject.

Judging by the evidence, the Society for the Suppression of Music was a joke created by Cincinnati artist Henry Farny and paper merchant John S. Woods. Completely humorous in intent, the Society gathered for regular dinners at which members read outrageous reports (some of which saw print in the local newspapers) and awarded each other facetious honors.

Newspapers as far away as Chicago picked up the gag and recommended that their cities should form satellite chapters. The tone (if I may be forgiven a musical metaphor) of the Society is reflected in a letter read at an early meeting:

“I have in my home an instrument of torture known as a piano. My sister performs upon the same, likewise my wife. Where are the liberties guaranteed to us by the Constitution of the United States and the State of Ohio? Something will come of this. I hope it mayn’t be human gore.”

The fulminations of the Society led the Cincinnati Gazette to editorialize:

“The fact that nearly every house has a piano is alleged as proof that we are a musical people, whereas these pianos are in general proof that our citizens have no musical sensations or possibilities. There ought to be a 4th of July bonfire of pianos; it would be a greater relief than the Declaration of Independence.”

At one meeting, the Society heard a letter suggesting specific punishments for musical infractions:

“Any man, woman or child over two years, caught whistling in the streets should be marched to the nearest glass factory and be made to blow for a living. Piano pounders should be forced to wear boxing gloves and give security to keep them on during the pleasure of the Mayor. The musical critic, who in describing an opera or a concert, writes one word more than the Chief of Police, or, in his absence, the Chief of the Fire Department can understand with the assistance of the Wharf Master, shall be taken to the largest establishment where boilers are knocked into shape, and be made to explain Wagner’s music of the future amid the clash of hammers and roar of riveters.”

Although the Society was active at the time the May Festival was in flower, the College of Music was being founded and Music Hall was under construction, the citizens appeared to take the lampooning of the Society in stride.

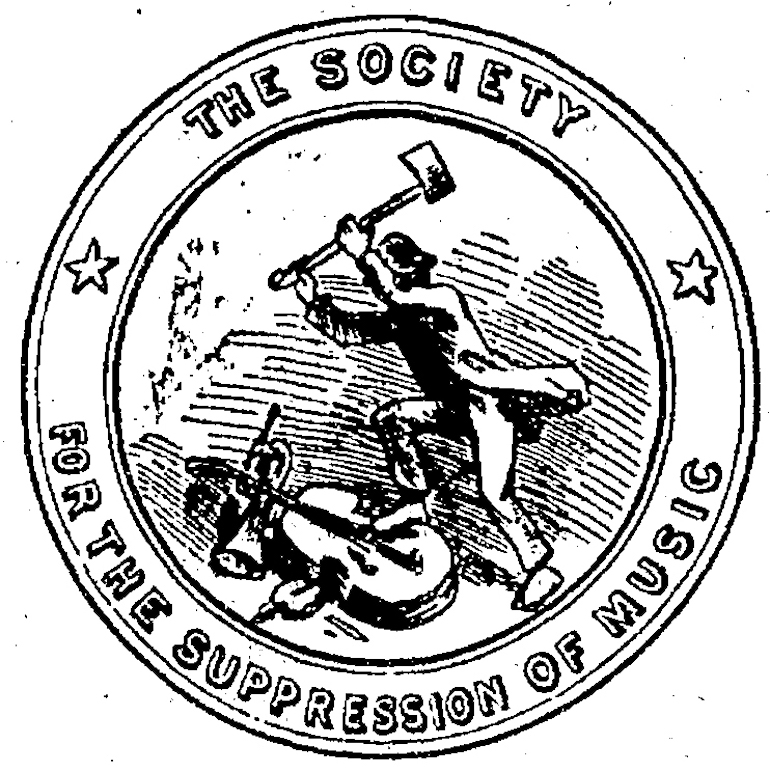

Newspaper reports of Society shenanigans were often accompanied by a reproduction of the Society’s insignia, depicting a man with an axe attacking a pile of musical instruments. Although later reports attribute the design to Judge Nicholas Longworth, it is almost certain that – whoever developed the concept – the execution was almost certainly Farny’s.The French-born Farny had lived in Cincinnati around 20 years when the Society was founded. Farny had, five years earlier, published a satirical weekly newspaper in Cincinnati titled “Ye Giglampz” with writer Lafcadio Hearn. He was about a decade away from the mature period in which he created the oil paintings of western scenes that have made him famous.

The Society’s claim about attracting “the best of our citizens” was not far off. An 1880 dinner was attended by Thornton Hinkle, Henry Farny, Dwight Huntington, Job E. Stevenson, Larz Anderson, R. Donahue, John Woods, G. W. Jones, Otto von Mohl, R. Warder, D. Holmes, P. H. Burt, W. A. Hall, Dr. Sinickson, C. Johnson, Bellamy Storer, Jr., and Edward Goepper.

Despite such membership, and despite the publication of Society jest and bombast in the newspapers well into the 1890s, just 60 years later, the Society for the Suppression of Music was all but forgotten. When a California correspondent wrote to Cincinnati’s Public Library, the staff could find no records of the society.

The appropriately named Cincinnati Librarian Chalmers Hadley tracked hints throughout the city, ultimately gathering enough information to prepare a brief paper for the Literary Club of Cincinnati in 1952. And then Cincinnati forgot again.

Leave a Reply

Lo siento, debes estar conectado para publicar un comentario.