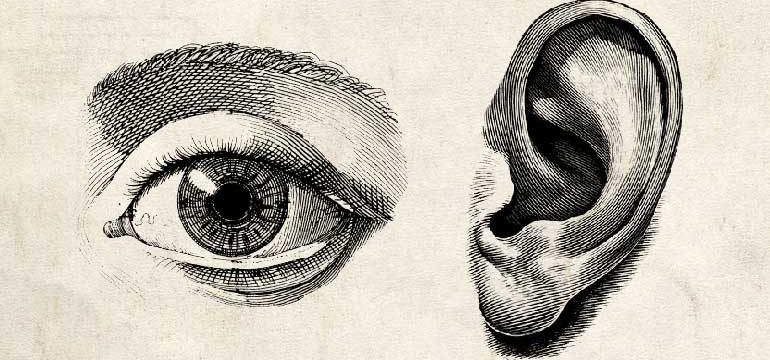

The perception of certain analogies between colors and musical sounds, has suggested to speculative ingenuity the possibility of giving to the eye a pleasure from the combination and succession of lively tints, similar to that afforded to the ear by the combination and succession of musical sounds; in other words, that there might be a visual music. It was observed that there were seven primitive colors, as there are seven notes in music; and that the same colors give us more pleasure in some combinations than in others.

This conclusion seems, however, to have been too hastily formed, and to have overlooked the great diversity between the senses of vision and hearing, both as to the sources of their respective pleasures and the degree of pleasure of which they are severally susceptible.

The pleasure which we derive from colors is almost wholly positive, while that from musical sounds is altogether relative to their combination. An object that is red, blue or yellow, is so independent of every other object, and the impression singly made by those colors upon the eye is always the same. But not so with musical sounds. The several notes of the gamut depend upon their relation to other sounds, so that the note or sound which would at one time be A, answers just as well for B at another, and C at a third. In short, any note whatever, in one combination of sounds, or in one scale, may serve for any other note in another scale, or another combination.

Again: the pleasure we derive from seeing single colors is greater than that from hearing single sounds. Clear and bright crimson, or scarlet, green, orange, or purple, cannot be beheld without affording the eye some gratification; but a single sound is heard with utter indifference. It is only by a succession of sounds that the ear can receive lively pleasure.

It is not, however, every succession of notes that can please. Sweetness or melody in music depends upon the particular successions of notes which are fitted by nature to please our organs of hearing; and while some of these series may afford us the liveliest gratification, other series may be heard with indifference, and even with distaste. But one succession of colors, if not the same, is nearly the same as another. Whether we look at red, yellow, and blue, or blue, red and yellow, or yellow, red and blue in succession, the difference is inappreciable.

The influence of every note in music is, on the contrary, affected by the notes which precede or follow it; and, whatever is the effect produced, the same effect would be produced by an infinite number of other notes, provided only they have the same relation to each other. But though any simple sound whatever may stand equally well for A, B, and all the other notes of the gamut, but one modi?cation of li ht can represent red, blue, or any other color.

Now as there is so great a difference in the mode in which pleasure is produced in the two senses, we should find no difficulty in admitting there may also be a great difference in the degree of pleasure they can respectively confer. Indeed, on the first mention of the subject, it would seem probable that if the eye had been capable of gratification at all comparable to that afforded to the ear by music, man, ever on the search for new enjoyments, would long since have discovered it, in the same way as he has shown himself in every stage of society, sensible to the pleasure of music, and has invented such a variety of instruments for ministering to that pleasure; and the rather, as the acknowledged pleasures of the eye, from reflected light and the prismatic hues, have been at all times sought by him with indefatigable zeal, in all the three kingdoms of nature. It is to procure this visual gratification that he has drawn gold, silver, and precious stones from the bowels of the earth, and pearls from the depths of the ocean—that he has converted one insect into the most brilliant dye, and the tiny web of another into his most beautiful clothing; and lastly, that no small portion of his labor is expended in staining, dyeing, painting and polishing.

But, on further inquiry, we can see causes for the livelier, though more transient pleasure of music. It is by a particular succession of musical notes that nature has taught man to express his stronger emotions. Every passion has its appropriate tone, or particular series of musical notes, which all human beings are instinctively prompted to utter, and instinctively able to understand ; so that the simplest words of a language, as go, come, yes, no, may be so pronounced as to indicate to every one who hears them whether they are spoken in joy or grief, in anger or good humor, in fear or confidence. There is thus, then, a connection, created by nature, between sounds and feelings, which does not exist between feelings and colors. Now by means of emotion, our sympathies may be appealed to and excited, and every exercise of them is more or less a source of pleasure, even when we have a fellow feeling with emotions not pleasurable, as when we compassionate the sufferings of others. Possibly, it may be found on a nice analysis, that melody in music consists in those successions of sounds which are best fitted for exciting our sympathies, and that the most melodious is that which calls up those sympathies that are the most pleasing.

But be this as it may, it is clear that nature has made a direct avenue to the human heart through the organs of hearing which she has denied to the organs of sight; and though she had not, it is very conceivable that one sense may be so constituted as to experience a liveliness of pleasure of which another may be incapable; and if water to a thirsty man, or food to a hungry one, can give an intensity of gratification which no pleasure from music could approach, as it unquestionably may, in like manner the ear may find a pleasure from certain series of sounds which no combination of colors can give. And if so much more labor and cost is expended in gratifying eye than the ear, it is because the pleasure afforded to the first, being embodied in permanent forms, can be repeated and renewed at pleasure, while those of music are lost the moment they are enjoyed, and require a repetition of the same human agency for every renewal of the pleasure.

There is yet another reason why the direct pleasures of vision should be inferior to those of hearing. The eye being the vehicle of sensations greater in number and variety than those of any other sense, it gives rise to a greater number of thoughts and associations. It probably furnishes nine-tenths of the materials of our mental operations. The consequence is that its powers being thus unremittingly tasked, its original pleasures are proportionately interrupted and diminished. This fact is shown by those who have gained their sight by being couched, and who have shown a sensibility to the beauty of color, form, and soft light that is never witnessed in ordinary eyes.

It won’t seem, then, that the notion of giving to the eye a pleasure from colors at all correspondent to that afforded to the ear by musical sounds, is visionary, and inconsistent with the unchangeable ordinances of nature.

«The Pleasures of the Eye and Ear Compared», G. T., American Quarterly Register and Magazine, May 1848, Vol. 1, No. I.

Leave a Reply

Lo siento, debes estar conectado para publicar un comentario.